Hagia Sophia has been converted back into a mosque, but the veiling of its figural icons is not a Muslim tradition

Christiane Gruber, University of Michigan and Paroma Chatterjee, University of Michigan August 18, 2020

Ever since the reversion of Hagia Sophia back into a mosque, the Muslim call to prayer has been resounding from its minarets.

Originally built as a Christian Orthodox church and serving that purpose for centuries, Hagia Sophia was transformed into a mosque by the Ottomans upon their conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

In 1934, it was declared a museum by the secularist Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

As of June 24 of this year, Hagia Sophia’s icons of the Virgin Mary and infant Christ are covered by fabric curtains as the edifice yet again changes functions.

Turkish officials have stated that the veiling of the images, especially the interior mosaics, is necessary to transform the interior into a Muslim prayer space.

As historians of Byzantine and Islamic art, we argue that in their rush to reassert the monument’s Islamic past, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his associates have inadvertently – and superficially – emulated certain Orthodox Christian practices.

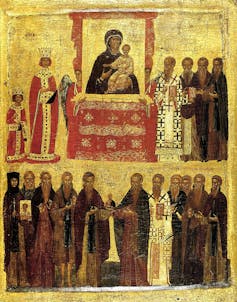

Images of Mary and Christ were often ritually veiled and unveiled in Byzantium, while later Ottoman Muslim rulers did not engage in such practices.

Images of Mary and Jesus in Islam

When Sultan Mehmed II, known as the “Conqueror” or Fatih, took over Constantinople, he headed straight to Hagia Sophia, declared it a mosque and ordered it protected in perpetuity.

He did not order the ninth-century mosaic of Mary and Christ in the interior removed or covered. Instead, Ottoman historians tell us that he stood in awe, feeling that the eyes of the Christ child followed him as he moved about the structure.

Although images of humans are almost never found in mosque architecture, the depictions of Mary and Jesus remained uncovered in the mosque of Hagia Sophia until 1739. At that time, the mosaic was plastered over. The plaster was later removed during the building’s 1934 conversion into a museum.

The centuries-long display may have been a gesture in appreciation of the Prophet Muhammad, who is said to have preserved an icon of the Virgin and Christ when he destroyed the pagan statues at the Kaaba, Islam’s holy sanctuary, in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

In this and other cases, Muslim rulers clearly understood that religious figures can be used for devotional purposes without necessarily being idolatrous. This nuance has been lost as of late in the more recent debates surrounding representations of the Prophet Muhammad.

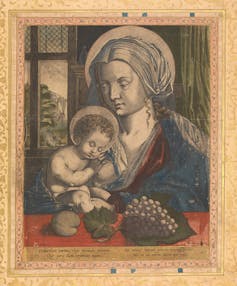

in an Ottoman album around 1600. The Metropolitan Museum

From the medieval period onward, Mary and Christ are in fact a recurring motif in Islamic art. They are depicted in metalwork, on glassware and book paintings.

European prints of the mother-and-child pair were also collected into albums by the Ottoman elites of Constantinople in the 17th century. Not shunned or destroyed, these images were sought after, safeguarded and even embellished with colorful paints.

Veiling icons in Christianity

In the history of Christianity, covering images, and revealing them at significant moments, often testified to their power. The wrapping, encasing, framing and veiling of the most precious images and objects signaled and guaranteed their divine qualities.

Thus relics were stored in containers and icons strategically enshrouded. Sometimes, paintings of Mary and Christ in medieval Western European manuscripts were screened by veils sewn onto folio pages.

Lifting these cloth “shields” enabled viewers a full visual and tactile experience of the divine depiction beneath.

Virgin Mary and Christ Infant flanked by fabric veils. The British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

The Virgin Mary, or Theotokos, as she was known in Byzantium, is closely associated with veils. The “maphorion,” or the cloth with which she is believed to have covered her head and shoulders, was housed in Constantinople. It was said to be invested with protective powers and believed to ward off enemies.

A Byzantine miracle

Turkish officials claim that the curtains covering the mosaics are on an electronic rail system and that they shall be lowered to cover the icons only during prayer times.

But if the strips of cloth covering the Mary and Christ mosaic are to be raised intermittently and nonmanually between prayers as proposed, then a startling – if purely cursory – coincidence would emerge.

[You’re too busy to read everything. We get it. That’s why we’ve got a weekly newsletter. Sign up for good Sunday reading. ]

It would resemble somewhat a well-known 11th-century Christian miracle in Constantinople. The story goes that each Friday evening, the veil covering an icon of Mary and Christ would rise by itself after prayers. It would remain lifted until the following day when it fell again – on its own.

The raised veil was interpreted, among other things, as a sign of the tangible interface between the divine and mortal worlds and, more specifically, as the Virgin Mary’s embrace of her devotees.

The paradox of the past

The rich symbolism of the 11th-century miracle and other instances of Orthodox practice is certainly lost in the current strategy of veiling at Hagia Sophia. Ideological struggles over this world heritage structure since 1934 reveal the extent to which the monument serves as a symbol for the staking of political power and religious authority among Christians, Muslims and secularists in Turkey and beyond.

This time around, rather than maintain Hagia Sophia as a monument of coexistence, the Turkish government’s actions have sharpened an already tense ideological divide between pious and secular Turks, and between Muslims and Christians worldwide.

But beyond the political and religious posturing, we argue that Erdoğan and his team have also accidentally, and speciously, brought back the fabric veiling of icons, one of the practices of Byzantine Orthodoxy.

Christiane Gruber, Professor of Islamic Art, University of Michigan and Paroma Chatterjee, Associate Professor of History of Art, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.